Interview with documentary photographer

Soumya Sankar Bose

His practice on photography is more like an anthropologist where he tries to enlighten on the life of certain people and their behavioural transition from past to present.

Interviewed by Debarshi Das

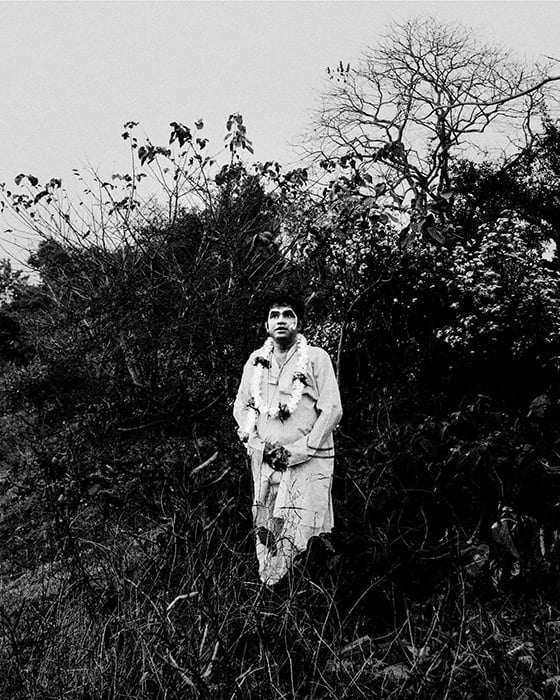

Photographs by Soumya Shankar Bose

Soumya Shankar Bose

A Kolkata, India based photographer, completed a Diploma in photography from Pathshala, Dhaka in 2013. His project, ‘Full Moon on a Dark Night’ was awarded the ‘Photography and Social Justice Fellowship’ by Magnum Foundation. He is also a recipient of grants from ‘Magnum Foundation’ & ‘Henry Luce Foundation’, and from ‘India Foundation’ for the Arts. His work got featured in various leading platforms. His first book ‘Where the birds never sing’ on Marichjhapi massacre will be published soon.

In this interview for Exposure, Soumya talks to our editor Debarshi about his journey of photography.

1. Let’s start from the beginning. You were born in a small city of Midnapore and started your education as an engineer but how you became interested in Photography?

Photography for me started way back from my schooling and we used to have a small group in Midnapore which had sown the seed of interest towards movies, art and literature. This, in turn, germinated my inclination towards photography or refined my visualization towards various aspects of photography. Also, my study of engineering in Calcutta around 2007 and transition from a small town to a big city with better scopes of internet facilities helped me to research on the things which were lagging during my stay in the hometown. But the momentous visualization happened during my years of study in Pathsala from 2011 to 2013.

I came to know about Pathsala during my 3rd year of engineering and got enrolled myself for the same after submitting my portfolio. It was a huge honour for me to get a scholarship back then from Pathsala, had there been no privilege of scholarship, then it would have been quite arduous for me to get through that prestigious school of photography.

2. Your photographs convey a strong presence and understanding of your surroundings. How this documentary and research styled photography attracted you?

I don’t believe in the word documentary styled photography. All photographs document something. My practice is more like an anthropologist where I try to enlighten on the life of certain people and their behavioural transition from past to present. In a nutshell, I am deeply motivated by the works of Svetlana Alexievich, Raymond Carver, Anton Chekhov, Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay, Sunil Ganguly and in movie directors like Emir Kusturica, Fellini, Wong Kar Wai, Tarkovsky, Kubrick, Orson Welles, David Lynch, Roy Anderson, Chantal Akerman and many more…

3. Later, you completed your post-graduation from Pathshala South Asian Media Institute, Dhaka, Bangladesh also. Pathshala is one of the most respected photography institutions in this continent and it has some legendary photography faculties. Tell me how the study of Pathshala has helped you with your kind of photography?

Pathsala was a very astounding experience and an amazing journey which had made me introduce with the history of art & literature amalgamated with exclusive access to 180 years of photographic history. There was hardly any concept of closed confined classroom theory in Pathsala with strict vigilance of teachers. There were more discussions between seniors and juniors of the same institution. We also use to have access to workshops conducted by renowned photographers who developed the inclination towards researching an incident and photographing the same.

4. One of your ongoing projects is Where the Birds Never Sing, is based on the Marichjhapi Massacre. What inspired you to take this challenge and what sort of change you are expecting to see in the societal establishment post completion of the same?

This project is very much close to my own life reason being my ancestral family who belonged to Bangladesh had also been evicted during the partition and took refugee in India. So, this project resonates my own root and about the people who have undergone a rigorous and bitter journey in their lifetime. Through this intricate amalgamation of facts and fiction of existing oral histories of the real survivors, I wanted to enlighten on the several perspectives of this blood-stained history which has been obliterated from the minds of the people.

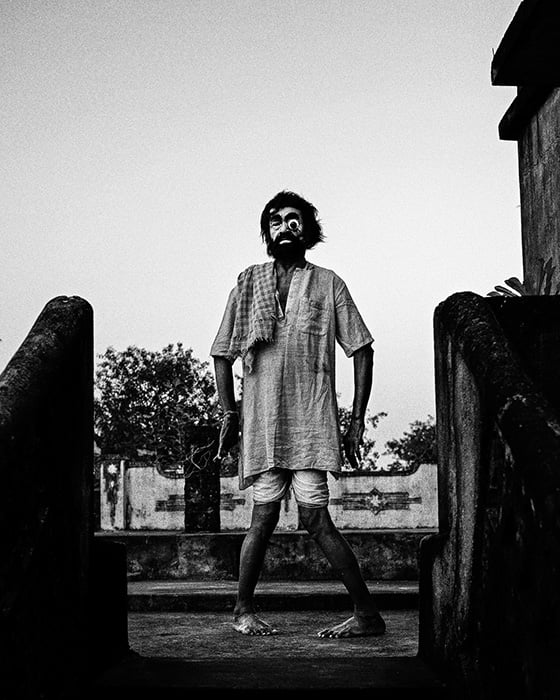

Since my previous project (Jatra) was about documenting an old generation group of artists who used to perform staged play popularly known as Jatra in Bengal Provinces, this experience helped me a lot in finding out people related to Marichjhapi incident. I had spent several months in Andhra Pradesh and Orissa researching into those people which made me aware of the loophole and failure of the governmental system.

I don’t think any artist can bring a huge change in the societal establishment; we rather document an incident which has the fear of getting erased in the pages of history. Our work might help the next generation or arouse an interest to study the lost history.

5. Please do tell us about the thought process of your very offbeat project: Full moon on a dark night. What sort of previsualization you had gone through before pursuing this project?

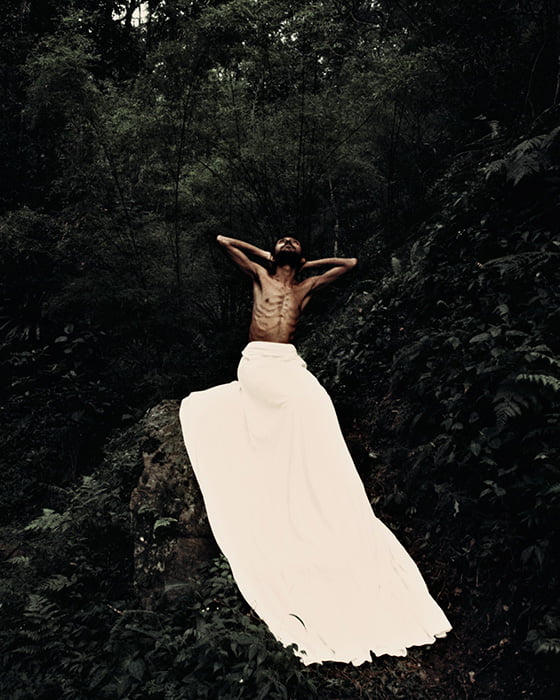

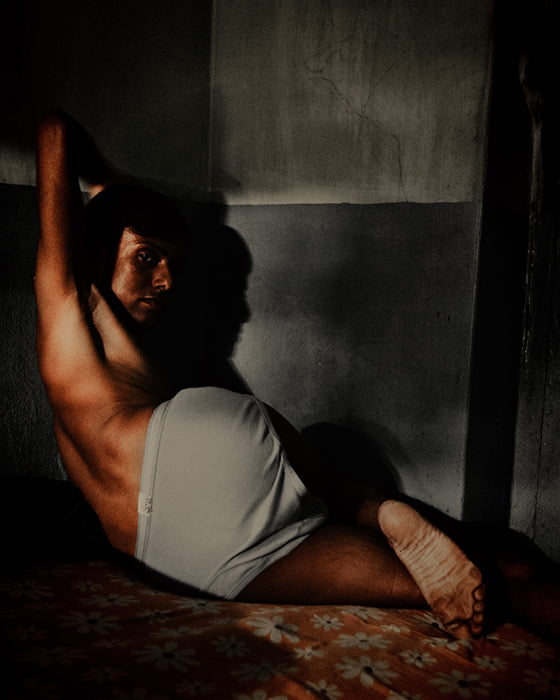

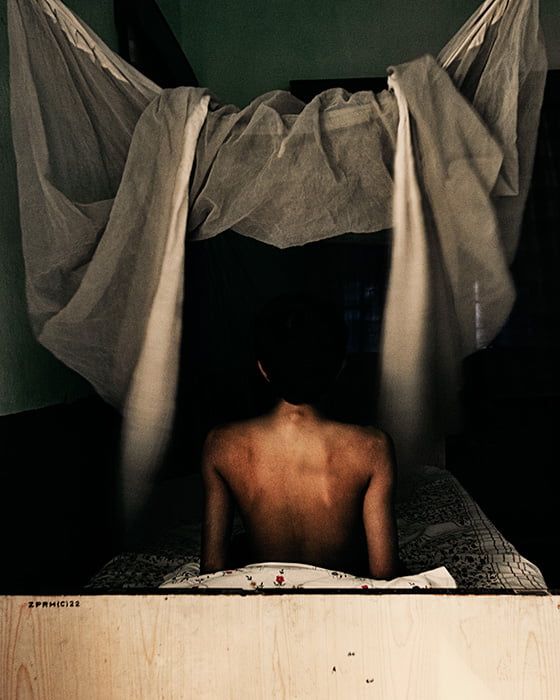

‘Full moon on dark night’ is also very personal which mainly deals with my lifeline and priceless possession called friends. They have always played a pivotal role in my photographic journey. Since my previous project Jatra was about those people who were of my previous generation, so the thought of documenting the experience of those socially persecuted people who were of my generation had struck my hypothalamus. Discussions with them on their day to day struggles and persecution by the society due to their own choice had arisen my grey matter to dig deep into their struggle for existence.

This work looks closely at the queer community of eastern India, often projecting a world devoid of restrictive laws and social taboos that the community regularly comes up against.

6. Are there any photographers who inspire your work?

There is a long list, I’m naming few important names here – Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Dayanita Singh, Nan Goldin, Diane Arbus, Francesca Woodman, Leigh Ledare, Stephen Shore, Gregory Crewdson, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Bharat Sikka.

7. Is there a specific moment with any of the works/stories which you have completed, that resonated strongly with you or your family?

Both ‘Jatra’ and ‘Where the birds never sing’ are very much intricated and weaved within my family and life.

My Grandfather and Uncle were very much associated with this staged play popularly known as Jatra. But there were hardly any recognition or documentation or archive regarding the same. So, it was very necessary to document those people’s lives who were a part of those infamous staged plays for more than decades in the Bengal Provinces.

8. Every person does not see the thing the way, a photographer can see. It’s our sole responsibility to view those rare moments and showcase the same to others. In order to do this, every photographer should carry some ethics which won’t destroy the original story of the frame. Do you believe these are being thought about and being taken care in the world of photography?

I don’t think photographers carry any power, rather there are various examples where they have been seen to misuse power. Someone’s carrying a camera and goes to document poor people’s life, they carry a hope that the person will document their hardships and bring it to light to some governmental institution, who in turn will help them but instead it always goes in the other way round. I hate this process, photographers can only document stories which will act as a source of inspiration for the next generation to study and research more about the lost history of time.

9. Being a photographer, what suggestive measure do you want our new generation photographers to keep in mind?

Try to weave a story out of the project you’re working on. You should dig deeper and spend more time on research than posting your images on social media. Photography is a solo journey unlike a movie, so it’s a sole responsibility of a photographer to document and showcase the history of hiding inside the grave full of stories.

10. Due to easy availability of phone camera and highly globalized DSLR market, the young generation has very easy access to this field. Is this affecting the sanctity of photography or improving the aspect of photography?

It’s been very interesting to see how the globalized market of image-making tools has helped in moulding every upcoming photographer who wants to take this challenge and to pursue any genre of photography. But I don’t think this is improving photography at anyway. This is just helping them to create content which is boosting up the followers in Instagram. But on the other hand, many are doing really great work without studying in any reputed institute. This is happening only because of internet, phone and social media.

11. Let’s wind up with discussing the social media aspect of photography. What are your personal thoughts on Instagram as an image-making tool? Is it really helping in extrapolating talents, but we can’t deny that it has been playing a significant role in shaping the future of photography?

I don’t think social networking will establish you as a photographer, you should rather use the same to promote your book or exhibition which are forthcoming on your calendar. But still, there are always some exceptions, but not many examples.